1948-2020

By Natalia Díaz and Juan Moreno

November 2020

We are immensely grateful to all the cattle farmers such as Félix León, Hermógenes Rivas, Reneldo Ojeda, and their families –they have stood by us from generation to generation working and projecting the land.

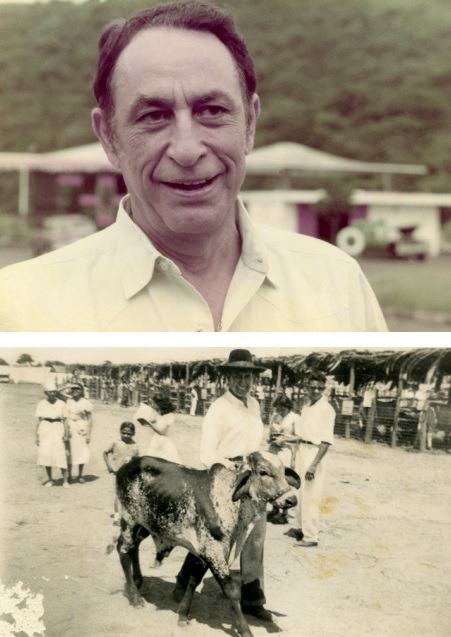

Alexander Degwitz Maldonado

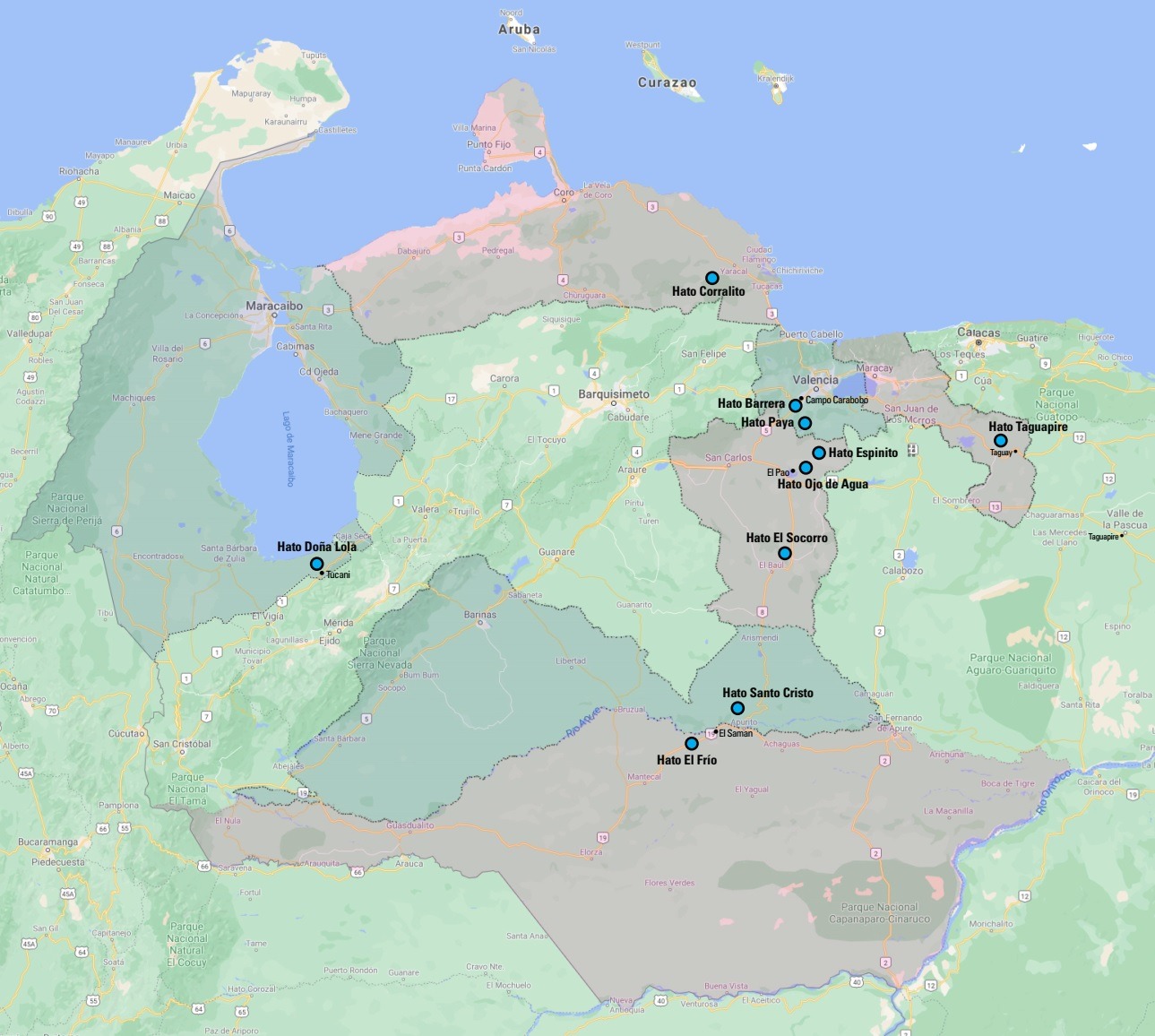

On October 29, 1948, the company Inversiones Venezolanas Ganaderas (INVEGA, C.A.) [Venezuelan Livestock Investments, A.C.] was created. Since then, and for over seven decades, it has been a key player in the development and modernization of livestock sector in Venezuela.

INVEGA’S creation was a critical step in the development of the Maldonado family’s ranching legacy. That journey had begun in the year 1911, with the acquisition of the El Frío ranch (then home to 2,500 heads of cattle[1]) by Dr. Samuel Darío Maldonado. He then moved on to buy the farms Santo Cristo, in the state of Barinas, and Los Yopitos in Apure. Dr. Maldonado was interested in improving the quality of beef cattle using crossbreeding and better grass for pasture. Among his initiatives were the acquisition of Angus cattle in 1913 and experimenting with the acclimatization of warm weather alfalfa, bringing the seeds from France and Peru[2].

Sadly, Samuel Darío Maldonado suffered an early death. His son, Iván Darío Maldonado Bello–lawyer and veterinarian—was left with the task of continuing his father’s work. Being only 29 years old, in 1942 Iván Darío buys the Paya ranch with the help of José Manuel Sánchez, his mentor. He intended to use it as a feedlot facility for El Frío’s cattle:

I had to learn how to offer the Apure cattle in more advantageous conditions for buyers. The slaughterers wanted heavier animals brought in smaller lots, so they could take the beef to clients when and where it was needed, and give them time to pay.[3]

Dr. Iván Darío Maldonado also understood the need to prevent the herds from losing weight during transit from Apure to Venezuela’s central region. He searched for new and productive farmland, sometimes allying with other ranchers.

THE BEGINNINGS

These continued efforts led to the creation of INVEGA in 1948, starting with a capital of 3,211,000 Venezuelan bolivars. The biggest contribution was made by Samuel Darío Maldonado’s successors, and the rest of the partners were already in business with Iván Darío Maldonado in other livestock ventures. A lot of the seed capital came from a large group of farms, ranches and real estate distributed all through the states of Apure, Barinas, Cojedes and Carabobo. The ranches El Frío, Los Yopitos, Santo Cristo, El Socorro and Barrera stood out among these properties.

The share distribution at the time of the company’s birth was the following:

| Lola Bello de Maldonado | 1.609 shares | Bs. 1.609.000 |

| Iván Darío Maldonado: | 818 shares | Bs. 818.000 |

| Ricardo Maldonado | 402 shares | Bs. 402.000 |

| José Manuel Sánchez | 157 shares | Bs. 157.000 |

| José Sotillo Guillén | 134 shares | Bs. 134.000 |

| Manuel Vicente | 47 shares | Bs. 47.000 |

| José Luis Bello | 34 shares | Bs. 34.000 |

| Francisco Bereciartu | 10 shares | Bs. 10.000 |

[C.A. INVEGA’s Constitutive act. Valencia, 10-29-1948]

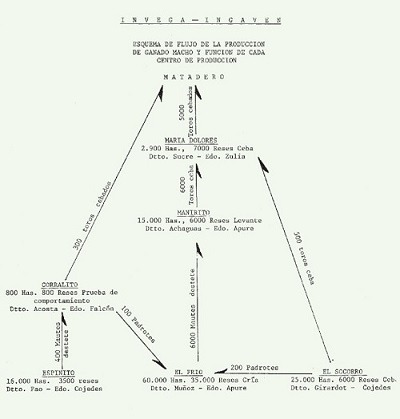

With its main headquarters located in the city of Valencia, C.A. INVEGA began its operation as a modern livestock company whose main objective was the commercialization and industrialization of cattle breeding to obtain and distribute beef and milk. Another goal was to conduct “scientific research on the different breeds of cattle and types of pasture, to understand their yield, how they acclimate and the diseases they’re prone to.” By 1955 there were close to 30,000 heads of cattle in the company’s property.[4]

From the beginning, INVEGA planned to acquire and improve land and facilities in order to have an integral breeding, calf rearing and priming operation, in the area comprised between El Samán de Apure and Valencia. This was done using state-of-the-art procedures and equipment, bringing in qualified staff, training local workers in the different areas of the trade and conducting research on cattle and pasture.[5]

One of the first important milestones for INVEGA was its participation, in the early 1950s, in the National Livestock Cooperative Society[6], created to promote the use of aircraft in the transport of fresh beef to the markets in the center regions of the country. The cargo was conducted there in DC-3 airplanes, and it was a way to move the cattle avoiding the ranches where the aphthovirus had spread. An airstrip was built in El Frío, as well as a suitable type of slaughterhouse.

INVEGA AND NELSON ROCKEFELLER

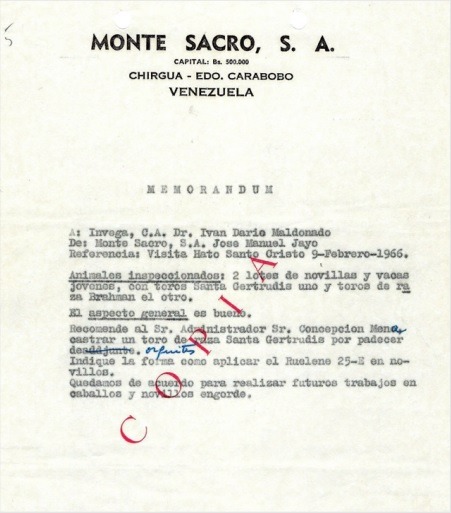

The friendship between Iván Darío Maldonado and Nelson Rockefeller –then governor of New York—, allowed INVEGA to enter in a partnership with the company NARFARMS and merge with it to create MALNAR LIMITED (Maldonado – Nelson Rockefeller). This firm was in business from 1962 to 1977. It’s worth underlining the contributions and participation of the veterinary Dr. José Manuel Jayo, as well as surveyor and pilot Miguel Fernández. From this point on, the Barrera ranch was taken out of the beef cattle operation and transformed into a dairy farm, and as such became the main provider for the company of dairy products Leche Carabobo, which later would be transformed into INLACA.

IMPROVING THE HERDS

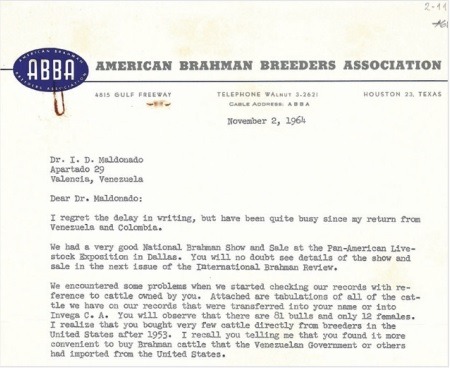

During its 72 years of existence, INVEGA has developed a successful cattle farming operation, focused on improving the herds with crossbreeding and the incorporation of new varieties of cattle. Dr. Maldonado made notorious efforts, starting in the 1950s, to buy the first Brahman heifers in Texas[7] and Louisiana—certified by the American Brahman Breeders Association— in search of a genetic adaptation of the Zebu breeds to the tropical climate. The breeds Gyr, Santa Gertrudis and Holstein were also imported in smaller quantities. They all played a part in the genetic improvements made. Iván Maldonado’s sons, Álvaro and Juan Maldonado, also participated in these operations:

In the 1970s we bought cattle from the American Alphonse Forbes, who owned a Brahman herd. Those cows were as big as trucks. I haven’t seen Zebu cattle with those genetic characteristics since. That herd was Mr. Forbes life. We brought it in a completely stocked airplane, in aluminum pens.[8]

Juan Maldonado Blaubach relates his version of the story:

Dad was among the first livestock farmers to acquire Brahman cattle. We worked hard to create a pure herd. We brought in two Brahman breeds—Manso and Imperator. I had to make two trips to Louisiana in the US, where there were big Brahman production ranches, to buy that cattle. We brought them in the stretched model of the Douglas DC-8, a turbine airplane. We also imported Quarter horses… We developed two backgrounding facilities for the Brahman cattle in the Paya and Barrera ranches. Steers that met the required breeding conditions were sent to the ranches Espinito and El Socorro for their strengthening, and the bulls that stood out were then moved to El Frío and Santo Cristo and joined the mixed breed herds.[9]

Big efforts were also made in INVEGA to develop a good equine population. Reneldo Ojeda, a pioneer in this subject, deserves special mention as the leader of these genetic improvements.

IMPROVING THE PASTURES

Since the 1950s INVEGA has been investing in agrostology studies and pasture improvement. In the beginning, efforts went towards cultivating the Brazilian grass seed Hyparrhenia rufa for internal use and national commercialization. The Barrera pasture (Brachiaria decumbens) was developed in Barrera, and later exploited; this pasture is characterized by deep roots and water-retaining leaves.

By the 1970s, in the Apure region, the rough and fibrous grasses of the Venezuelan Llanos [plains] known as chigüirera had been displaced by the cultivation of the legume Macroptilium gracile, which was also called the ‘Maldonado’ legume by the Department of Primary Industries and Fisheries of northern Australia[10]. What made it possible to grow these pastures was the artificial extension of the rainy season conditions by constructing modules –which measured over 100 km—of banks and dams. These were used to avoid flooding and to ensure water supply throughout the dry season, as well as to enhance the terrain’s containment capacity. Álvaro Maldonado relates:

There are two types of grass in the shallows. The water grass, which is eaten in big quantities and is very filling for the cattle, but not very nutritious since it’s mostly water; and the lambedora grass [Leersia hexandra], more fragile and hard to maintain because if it doesn’t get light or stays in cloudy water for too long, it dies –the water needs to be constantly supervised. The lambedora is the best one because it carries the most nutrients –one kilo was much more effective than the same quantity of water grass, which was being cultivated in bigger quantities. So, we focused on perfecting the lambedora. We were at the forefront of the work with legumes. They also fertilize the soil, increasing biomass production significantly.[11]

BONSMARA, A SOUTH AFRICAN BREED

Looking to optimize the production and wanting to observe one of the best cattle operations in the world, Dr. Maldonado travels to South Africa intending to incorporate Bonsmara cattle–a mixture of the Shorthorn, Hereford and Afrikaner breeds—to INVEGA’s herds. After exchanging information with Dr. Jan Bonsma about the bovines’ adaptation to the environment and after making a diagnosis of the animals, they created a manual of selection by fertility (or diagnosis chart) for the INVEGA administrators.

José Luis Bello Nieves recalls:

Nearly 2,000 cows died every year in El Frío, but when Dr. Bonsma came to visit he helped us reduce that number. The exchange of knowledge with South Africa, added to the education Álvaro, Juan and I got in the United States, were crucial for INVEGA’s technical transformation and modernization.[12]

During this learning period, Dr. Maldonado and his sons studied the animals’ feeding habits, putting a lot of focus on the pasture. It was already macrobiotic, meaning it wasn’t only composed of macro and microelements—it also included bacteria that became active in the gut flora, which in turn helped the bovines digest the grasses and legumes. Dr. Bonsma incentivized those bacteria using a nutritional product called Rumevite.[13]

Iván Darío Maldonado then buys a food factory to start manufacturing Rumevite, leaving the management to his son Marcos. Juan Maldonado Blaubach relates: “I was able to use this concentrated and solid animal food in Barrera, and observed how it helped the dairy cows produce more. The product was made especially so they could consume it by licking it.”

INVEGA excelled in many shows accross the country for its bulls and heifers, getting to be the leader in sales of the Valencia fairs. Horses for the coleo[14] were also presented. Doralys Ojeda relates:

INVEGA got the best scores in the shows for many years. We had a bull named Campeón, who won around seven times. Every ranch was represented by a group of workers. We participated in a lot of parades which featured 40 uniformed riders perfectly aligned. My dad was very strict because controlling a horse is not easy –‘His head is crooked, straighten it; one horse behind the other, all horses straight’. Since I was little, I was always the queen of the fair of the INVEGA group”.[15]

THE PRODUCTION CHAIN

A popular saying, still commonly heard, states that “by traveling through Iván Darío’s lands you could cross Venezuela”. This remark has its origin in the production chain INVEGA implemented, using the basic cow-steer modality – after weaning the steers were taken to ranches in other zones where they would finish their growth before the feedlot. The Apure steers were mobilized to the plains in Barinas and Cojedes, where they reached their best size and muscular volume. Then they were moved to the country’s Coastal Range to be fattened and had their stellar moment south of the Maracaibo Lake, at the Doña Lola ranch. Finally, they were marketed directly, focusing on the commercialization of the live steers. The first-rate beef carcasses were sold in second place, along with the capybara meat.

Livestock was herded through the land to the central region for over four decades, so when commercial air transportation was introduced it was crucial for INVEGA’s progress. Since the 1940s Iván Darío had started to introduce civil aviation practices to improve the operation. Fernando Maldonado, his grandson, tells us:

After World War II, Dr. Maldonado brought DC-3, Curtiss and DC-6 planes into Venezuela to move the El Frío cattle, because at the time there were no internal highways to connect the different states of the country. That’s why a massive landing strip was built in El Frío, as well as the adjacent slaughterhouse. Also, the aviation company Ramsa was created and started to ship beef from the slaughterhouse to Maiquetía, Curazao, Cuba and Miami, until internal roadways were built in Venezuela. This resource, in addition to the administrative advances, allowed for INVEGA to remain present in all the ranches, since it made it possible to visit them all in one day.

One of the most productive times for INVEGA began with the incorporation of the María Dolores ranch in 1976. This 7,000 hectare farm was located in the town of Tucanizón, Zulia state, between the Andean piedmont and the Maracaibo Lake. It had clear and fresh mountain water sources, which irrigated pasture through a series of channels. After the grazing of the cattle, the pasture was flooded. Juan Maldonado Blaubach relates: “It was the best priming farm we ever had. At one point we were receiving the whole population of El Frío–more than 7,000 steers—to be fattened in María Dolores.”

Latterly the ranch was confiscated by the government, and INVEGA had to redefine its production route once again. Alexander Degwitz Maldonado recalls the need the El Frío ranch had for a priming farm:

After the expropriation of María Dolores by President Carlos Andrés Pérez, it was imperative to find a feedlot location for the considerable amount of raised steers. We focused our efforts on El Socorro and worked on improving the priming capacity of the Corralito ranch.

THE CAPYBARA

El Frío was the biggest capybara farming operation in Venezuela, with 7,000 salones[16] produced in a year. Their skin was exported to Bogotá and to Gloversville, New York.

Supervised by environmental specialists, this was the first ecologically viable model of capybara handling in the world. The anatomy, biology and behavior of the El Frío’s capybara population were studied with the participation of Dr. Juhani Ojasti and Dr. Tomás Azcárate y Bang, along with the Central University of Venezuela, the Ibero-American University of Sevilla and the Amigos de Doña Ana association—in addition, of course, to INVEGA’s support.

ECO-CONSCIOUS FARMING

INVEGA has put a great deal of emphasis on the preservation of the environment, especially of the tropical grassland plain ecosystems of the Venezuelan Llanos. The company has been mindful of its natural surroundings in its endeavor and it has respected the strict international conservation regulations. There had been many well-known initiatives to help guarantee the survival of the Llanos’ indigenous biodiversity, including some endangered species like the Orinoco caiman and the anteater. Also, the push and custody for the reappearance of the jaguar and the otter or perro de agua.

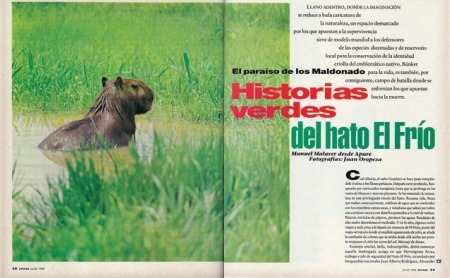

At the beginning of the 1970s, El Frío’s Biological Station (Estación Biológica El Frío) was set up thanks to the partnership between INVEGA and the Spanish non-profit Asociación Amigos de Doña Ana. It was coordinated by Spanish biologist Javier Castroviejo Bolívar. For over three decades this biological station was the site for important activities of research, education and divulgation about the Llanos ecosystem, as well as groundbreaking rescue programs for endangered species—the Wildlife Refuge, the fishing reservoir and the conservation area Caño Cuaritico. Its goals were to preserve the hydro biological systems, to safeguard a great variety of flora and fauna and, most importantly, to bring back the Orinoco caiman from the brink of extinction. Over two thousand caimans were released between the years 1989 and 2008, thus saving the species. This program was led by the biologist José Ayarzaguena.

In an interview with the journalist Ramón Hernández in 2010, Dr. Iván Maldonado described the biodiversity of the 76,000 hectares Apure property:

Forty-six thousand heads of cattle coexisted and reproduced in the same grounds as 12,000 horses, over 7,000 deer, a few thousand capybaras and 34 varieties of bats, as well as various endangered species like the Orinoco caiman, the giant otter and the anteater. Other protected species like the puma and the river dolphin also found refuge in the ranch’s land. There were also the biggest water snakes or anacondas, the spectacled caiman or baba, howler monkeys and over three hundred bird species which competed in color and exuberance— the little egret, the ibis, the white stork, the hoatzin, the scarlet macaw, roadside hawks and the peevish jabiru. It was also common to see jaguars and pumas in the gallery forests.[17]

Extensive cattle farming following good environmental practices was also applied in other ranches. A firebreak line was excavated to protect the woods, as well as the seven water sources of the Pao Cachinche reservoir. Dr. Maldonado wrote many times to various government ministries denouncing the provoked fires and other harmful practices that affected these pristine watercourses. These letters can be found in the family’s Historical Archive.

The feline presence was respected at the El Socorro ranch due to the wildlife corridor created for the jaguar (Panthera onca), an endangered species. These jaguars took shelter in the caves of the Terecay and Chiriguare hills, located in a meander of the river Cojedes. There are records of cattle being lost because of these animals, but despite this, they were never hunted. On the contrary, they were protected.

INTRUSIONS, DESTRUCTION AND LEGAL ACTIONS

Intrusions and cattle raiding start to happen in the 1980s in farms all over Venezuela. Later, in the first decade of the 21st century and under the banner of a revolutionary and socialist government, various ranches that were part of INVEGA’s productive chain were confiscated or occupied –sabotaging the highly developed and integrated operation that took place in the different properties, including cow-calf, backgrounding and feedlot farms. Many legal efforts were made to save and protect the land. A group of lawyers specialized in pastoral farming law was formed, and their actions were recorded in a narrative of great historical and juridical importance.

These illegal actions brought about an 80% reduction of the company’s land. The Espinito and Taguapire ranches were marked as idle land on January 7 and June 2, 2009. The El Socorro ranch –where the ASOCEBU[18]-certified Brahman cattle grazed—was plundered in 2008. The confiscation order for the El Frío ranch was issued on March 31, 2009. It was seized at a time when it was producing 1,812,000 kilos of beef and had a population of 3,823 steers destined for backgrounding and feedlot. Additionally, most of the Barrera ranch’s land was confiscated even though it wasn’t part of INVEGA, and despite its status as Area under Special Administration.

INVEGA REINVENTS ITSELF

In the last decades, INVEGA has ventured into rustic cattle—a type of livestock especially prepared to adapt to the tropic. It has also joined the buffalo farming industry to increase milk production, along with artisanal cheese manufacturing and double-purpose breeding (for dairy and beef).

An intensive dairy farming operation is inaugurated in 2008, using F1 heifers obtained by crossbreeding Brahman and Holstein cattle. This hybrid strength allows for the merging of the white cattle, specially adapted to the tropical climate, and the European breeds, which have a high capacity for milk production. Five hundred Brahman heifers were contributed by El Frío, Espinito and El Socorro to be artificially inseminated by Bos primigenius taurus breeds like Holstein, Brown Swiss and Jersey.

Other activities include cultivating cereals (corn and sorghum) to feed the F1 cows during the dry season, optimize intensive farming management and achieve the rotation of grazing modules with load monitoring for the optimal use of pastures.

IN HARMONY WITH NATURE

After four generations, INVEGA continues to provide work to descendants of its founders and original workers, who keep being a part of this family-run company. As a company that contributes to Venezuela’s economic development and agrifood health, INVEGA endures with resiliency and continues to reinvent itself. It keeps fighting for a farming practice in harmony with nature, thanks to the strength and committed effort of its workforce. Even in its reduced form, it endures –solid, like a light of hope in the darkness, and carrying a seed of future that can take Venezuela closer to becoming a sovereign and self-sufficient country.

——————

This work was sourced mainly from the testimony of this story’s protagonists, as well as the documents that make up the Maldonado Family’s Historical Archive (MFHA). This archive is divided into five subjects that tell the story of the interests, development and evolution of the corporate, financial and social aspects of the Maldonado family –genealogy, family property in the state of Táchira, livestock farming activities, company life and corporate social responsibility. The study and cataloging of the MFHA are still ongoing, so this story will keep being written.

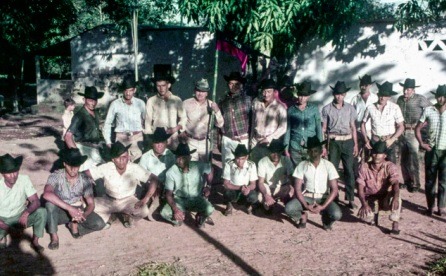

INVEGA workers.

“The purchase of the El Frío ranch came about because of the recommendation and encouragement offered by Ricardo ‘Tío Rico’ Bello Torres—Iván Darío’s uncle—who also managed the farms before his nephew took over the administration”.

Juan Maldonado Blaubach, 2020.

Document No. 350 – AHFM. Maldonado Family’s Historical Archive.

“I was born in the Santo Cristo ranch, owned by Dr. Iván Darío Maldonado, in a hamlet called El Toro in the state of Barinas. I lived there until the age of 11. Later, I started working as a receptionist at the first INVEGA offices, located in Cantaura Street near La Candelaria’s church [city of Valencia]. Next door to the offices there was a bookstore owned by a cousin of Dr. Iván called Virgilio. Latterly we moved into an old casona[1] in Peña Street which had been renovated to accommodate the offices. From there we communicated with all the ranches via radio”. Juana Ortega, former assistant to Iván Darío Maldonado.

[1] Big, stately house. Translator’s Note (TN).

Census Registry Act for the El Frío Ranch, presented by Ricardo Luis Bello in 1919. Document No. 365 – MFHA. Maldonado Family’s Historical Archive.

[5] “In the year 2000 INVEGA signed an agreement with the Agronomy Department of the Central University of Venezuela to conduct joint research, as well as extension and education activities, on agricultural technology. This alliance was the catalyzer for many undergraduate and postgraduate thesis about genetic improvement and herd yielding, among other subjects.

““INVEGA was a great school, a great family. Mine is the third generation of invegueros [INVEGA workers] in my family. My grandfather, as well as my father Félix León, both worked in El Frío. My father was a path cleaner and worked the slaughterhouse when they shipped the beef in the airplanes. Over time he specialized as a mechanic and operator, and in 1970 Mr. Maldonado arranged for him to go to Germany for three years to study the viability of using dredges to deepen the lakes so they wouldn’t dry out in the summer. [The dredge] was 9 meters long and 5 meters wide. The pieces were brought in and it was assembled here.”

Edgar Zambrano, worker of the El Frío ranch.

The Maldonado legume.

““At the Barrera ranch we started to harvest, dry and bag the Brazilian seed Brachiaria decumbens. It had so much success in northern Venezuela that it started to be known as the Barrera grass. This pasture was effective in eradicating the invasive weed known as escoba [broom]. We were pioneers in this regard.”

Juan Maldonado Blaubach.

““Everybody liked the beginning of the summer because it was possible to move the cattle; also, there was still green grass left from the winter. My father bought the farms that were located in the way, so there were ranches all through the herd’s journey. The herds left El Frío to go to the Santo Cristo ranch, then to El Socorro and finally ended up in the Barrera or the Espinito ranches. That way the cattle had to endure less travel and could be taken to the market in a shorter time.”

Álvaro Maldonado Blaubach.

Farmworkers at the Santo Cristo ranch.

“The Espinito ranch was one of the stops in that long journey from Apure to the central region. This farm had an array of very special conditions, one of them being its dry climate—it kept out the diseases and pests typical of the more humid areas. The cattle were brought there to be purged of all its parasites, and then it was ready to be primed”.

Juan Maldonado Blaubach.

Álvaro Maldonado and his daughter Verónica.

Exceso magazine, 1992. Document No. 2043 –MFHA.

“INVEGA’s branding iron had the shape of a tiger’s paw. Around the plains, it was common to hear the phrase “la mano del tigre se respeta [the hand of the tiger deserves respect]”. Also, the herds were identified by putting an earring in the cattle’s ears, which is why the earring is another unmistakable INVEGA mark”.

Juan Maldonado Blaubach.

© INVEGA C.A / Grupo Económico Maldonado (GEM). November 2020.

Production: Natalia Díaz.

Design: Katalin Alava.

Editing and proofreading of the Spanish version: Sara Pignatiello.

Translation: Sara Pignatiello.

Photos: Carlos Acosta, Tony Croceta, Elizabeth Degwitz, Alvaro Maldonado and the MFHA.

[1] Document No. 350 – AHFM. Maldonado Family’s Historical Archive.

[2] Document No. 352 – AHFM. Maldonado Family’s Historical Archive.

[3] Document No. 291 – AHFM. Maldonado Family’s Historical Archive.

[4] Document No. 512 – AHFM. Maldonado Family’s Historical Archive.

[6] In Spanish: Sociedad Cooperativa de Ganadería Nacional –GANACO.

[7] Document No. 689 – MFHA. Maldonado Family’s Historical Archive.

[8] Álvaro Maldonado. Interview with Natalia Díaz and Dharla Maldonado. March 2018.

[9] Juan Maldonado Blaubach, personal communication. October 2020.

[10] Cameron A.G (1992) “Maldonado registration description”. Australian Journal of Experimental Agriculture, 32:264.

[11] Álvaro Maldonado. Interview with Natalia Díaz and Dharla Maldonado. March 2018.

[12] José Luis Bello Nieves is Tío Rico’s grandson and was INVEGA’s manager for over 15 years. Interviewed by Natalia Díaz and Sol Rivero. July 2018.

[13] Document No. 3037 – MFHA. Maldonado Family’s Historical Archive.

[14] Traditional Venezuelan sport in which a group of cowboys on horseback chase after a bull and try to make it drop or tumble. Translator’s Note (TN).

[15] Documents No. 599 and 605 – AHFM. Maldonado Family’s Historical Archive.

[16] The dried meat of one capybara is called salón in Venezuela. TN.

[17] Hernández, Ramón (Oct, 2010): “Hato El Frío, Historia de un despojo” [“El Frío ranch: the story of a plunder”]. Document N° 2454 – MFHA. Maldonado Family’s Historical Archive.

[18] ASOCEBU stands for Asociación Venezolana de Criadores de Ganado Cebú [Venezuelan Association of Zebu Cattle Breeders]. TN.

Recent Comments